The Indian Workers’ Association (IWA) was founded with a variety of multi-faceted aims. Initially, their work promoted India’s liberation from the British Raj, whilst also providing a hub and meeting place for Indians within Britain. Its international political aims were thus integrated with its domestic purposes; the movement formally established in Coventry in 1939, aimed at making changes both to the everyday lives of its members and changing the global landscape.

The IWA reached its peak in the postwar period, but it was between the First and Second World War that Indian, principally Punjabi, immigrants started to arrive in noteworthy numbers. They worked in a variety of jobs, from peddlers, selling their wares on the streets and at markets, to factory workers, laboring amongst the rattling of machinery. Work places were often highly politicised and in some cases radical environments. In the context of the Great Depression, trade unions were key political players, fighting hard to represent their members, as unemployment rocketed, and poverty along with it. Yet intolerance was also a staple of the workplace and an uncomfortable feature of many trade unions. Immigrants were, in some cases, explicitly excluded out of trade unions and prohibited from membership. At its inception in 1938/39, the IWA was designed to step in and fill this void in the lives of Indian labourers.

On account of its industry, particularly textiles and motor industries, Coventry was one of the first significant hubs of South Asian and Indian immigration. After its founding at a residential house, the IWA held its meetings mostly within its members’ homes. In this way, the early IWA seems to have been more than merely a workers’ association, transcending the border between the world of work and the personal and domestic environments of their members. Linking the public and the private in this way allowed the IWA to take on characteristics of a support network and a community group for the small Indian population. The IWA was not just a workers’ group, functioning in public places and the world of work; its aims and ideas stretched into the homes and personal lives of its members, setting it apart from the rigid organisation of other larger trade unions and workers associations.

Even as numbers of immigrants swelled after the end of World War Two, and IWA branches were set up across the country, (the Birmingham and Southall groups, for example, soon surpassing the Coventry group in terms of size and infrastructure,) overall, it seems that the organisation maintained its emphasis on acting as a support network for the welfare of its members. The immigration policy adopted by Clement Attlee’s Labour government, of encouraging immigration from the Commonwealth, made up of the former territories of the British Empire, saw immigration from across the globe. Britain had once stretched its power and brutal authority over a quarter of the world, but now opened its doors to different communities, cultures and races. The arrival of Indian immigrants in this period contributed to the steady growth of local IWA branches, which united to form the Indian Workers’ Association of Great Britain, IWAGB, in 1958. Estimations put membership as peaking somewhere around 20,000 people, however the actual figure is disputed.

Yet, even as numbers climbed, the IWA continued to play a prominent and supportive role in the lives of its members. Newer immigrants, who lacked English language skills, benefited from the use of translators and the social network the IWA provided for those who lacked familiar support and connections within their new home. As Talvinder Gill points out, acting as translators and pastoral support for newer members gave the IWA, “a great deal of power to influence the political direction of the emerging local Indian population”. By acting as a bridge between the British Indian community and wider English-speaking society, the IWA could provide both practical and political advice, directing more recent immigrants away from certain unreliable employers, but towards radical workplace politics. The pastoral function of the IWA appears to have been a necessary mechanism in allowing the movement to grow, harnessing the waves of Indian immigration to the organisation, through the involvement in the personal and social lives of immigrants.

This social network also accelerated the development and celebration of Indian arts and culture within the UK. Several IWA groups used cinema, in particular, to bind its members together, giving them the chance to celebrate the culture of India in their new homes. Films would be imported or rented from the Indian High Commission and screened in cinemas specially rented out for members. The Southall branch of the IWA even purchased the Dominion Cinema in 1965, with the aim of turning it into a hub of South Asian and Indian cinema. Part of the money to buy the cinema was raised from donations by local and national IWA members, amounting to around £25,000. In its prime, 8,000 people descended on the Dominion Cinema a week, coming from right across the country. A decline in income, however, led to the Southall IWA leasing the cinema building to Ealing Council. South Asian cinema continued to be used as a valuable tool in creating links amongst members and the wider community, beyond the scope of a traditional workers’ association or union.

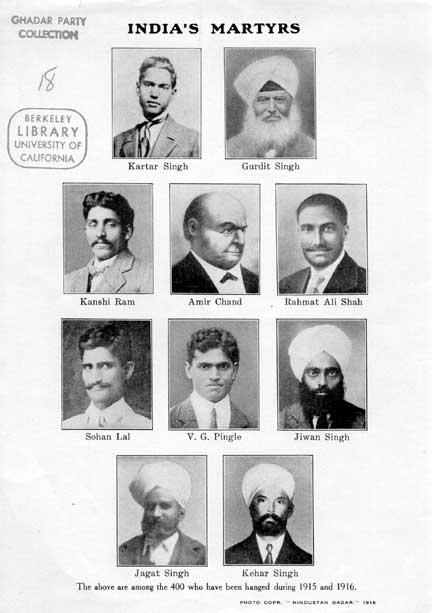

Following on from the activism of the Ghadar Party, founded on the Pacific Coast of North America, and the Communist Party in India, the IWA saw itself as descended from an illustrious tradition of Indian radicalism and anti-colonialism. The movement’s questionable and widely disputed links with revolutionary Udham Singh, assassin of Michael O’Dwyer (the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab during the 1919 Jallinwalabagh Massacre) added a mysterious lustre to the IWA’s history and place within this radical politics, helping it to depict itself as the latest iteration of this rich tradition. The Ghadar Party, though oriented towards and focused on liberation from the British Raj, saw the value of tapping into workplace democracy and the politics of Indian labourers on the Pacific Coast of the USA and Canada. Lumber mill workers and agricultural labourers were a significant source of support for the Ghadar Party, thus, marrying anti-colonialism with class politics. The Communist Party of India, founded in 1925, was the embodiment of this combination, linking class oppression to imperial oppression far more explicitly than the Ghadar Party had done. The IWA sought to continue in this mold, yet its commitment to class politics sometimes caused conflict with its anti-racist agenda.

The dual focus of the IWA on the politics of both class and race did, however, cause a number of the frequent and often infamous ruptures that checker the organisation’s history. Though seemingly interlinked, many members and branches argued for a stronger separation between the IWA’s Marxist and anti-racist agendas and a firmer focus on the latter. Gurharpal Singh and Darshan Singh Tatla describe the IWA as having a “hardened communist ideology”, emphasising building class-consciousness amongst its members. The Southall branch cited this in withdrawing from the IWAGB in 1961, complaining of the preoccupation with Marxist ideologies. Yet fundamental to the IWA’s role and character was this fusion of class and race politics, a careful balance had to be struck to ensure that these joint causes were kept in harmony moving forwards.

Though over 4,000 miles away, the membership of the IWA was also split in line with developments in South Asia. In an interview conducted in 1993 one member, Anant Ram, recalled how Partition in 1947 and “split” the members and contributed to its decline, which lasted into the 1950s until the organisation was revived by another wave of migrants. Indeed, as the definition of ‘India’ changed, it seems inevitable that the extent of those who sought membership and identified themselves with IWA would change. Punjabi members had hitherto formed the majority of the ranks of the IWA, but as the state was ripped in half by the Radcliffe Line, Punjabi South Asians were split between India and the new state of Pakistan. From Partition onwards, the IWA continued to be impacted by political events in South Asia, its unity frequently being shook by developments abroad.

However, in spite of both ideological and national divides; the national membership of the IWA frequently came together to fight against workplace discrimination and other labour-related disputes. In its role as a workers union, the IWA was formidable and had extensive successes, rallying workers around its leadership. Fighting issues including segregated facilities, low pay and racist work discrimination, the IWA was behind several mass strikes, particularly in the Midlands and the South. The organisation lent their support to the strikes at the Midland Motor Cycle Factory in 1968 and during the labour disputes Dunn’s factory in Nuneaton, between 1972 and 1973, amongst other industrial actions across the country. The IWA was also involved in high-profile attempts to overturn the ban on turban wearing within the transport profession, reportedly spending around £60,000 on the campaign.

In the context of the radicalism of the postwar environment, the IWA was involved in a chorus of radical, anti-racist and anti-imperial movements, which reached its peak in the decades after the end of World War Two. As the world was finally largely decolonised and the fight for civil rights played out all over the globe, the IWA was an important organ for British South Asian communities in battling the racism so deeply embedded in British society. The IWA stood alongside a number of anti-racist groups, particularly in the period when the American and, eventually, global Black Power movement reached its peak. Black Power advocated a radical approach to dealing with the racist structures of everyday life and preached having pride in one’s racial identity. These were messages that the IWA willingly tapped into, combining its own radicalism with support for British South Asian communities and other marginalised communities.

In the age when ‘No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs’ signs adorned windows and doors, the IWA was instrumental in standing against some of the most notorious racist individuals and organisations of 20thcentury Britain. As Enoch Powell prophesied of “rivers of blood” and the National Front urged all immigrants to leave their country, the IWA frequently took to the streets to speak up for respect and equality for all. The IWA group in Southall spoke up in opposition to the Ealing Council allowing the avowedly racist National Front to host meetings in the town hall in April 1973. When they were unsuccessful, the group held a march through Ealing, alongside other anti-racist organisations, including the Anti-Nazi League. Though the demonstrations were peaceful, over 2,000 police officers deployed and things soon took a turn for the worst. Teacher, Blair Peaches, attended the demonstrations on 23 April and was struck on the head by a member of the police’s Special Control Group and died in hospital later that night. His body was laid in the Dominion Cinema, before his burial, which was attended by approximately 10,000 people. Peaches’ coffin was carried by turbaned Sikhs and members of the Southall Asian community, as well as white anti-racist allies.

Though the IWA has played a central role in anti-racist activism and workplace democracy in 20thcentury Britain, critics have argued that its work was limited in important respects. Talvinder Gill points to the IWA’s mixed record on women’s rights and caste-related issues. Despite its Marxist approach to class, caste prejudices and allegiances still overshadowed many IWA members – consciously and unconsciously. Though the organisation did attract members of all castes, it was mainly comprised of Jatt Sikhs and failed to make any real ground on caste discrimination within the UK. Similarly, as a male-dominated organisation, Talvinder Gill goes on to claim that the IWA were largely inactive on women’s rights struggles within the home and family setting regarding domestic violence and sexual abuse- areas which Gill claims were seen as “private”. The IWA does have a very strong record at standing up for women’s rights within the, perhaps more comfortable, context of the workplace. For example, the proliferation of sweatshops across the UK, which were often owned by Asians and employed Asian women, was met with condemnation by the IWA and its membership.

The IWA’s campaign against the degrading gynecological (‘virginity tests’) examinations conducted on immigrant women entering UK airports, is worthy of note in the way it dealt with such an uncomfortable and degrading issue. Claims that one such ‘test’ was used against a British-Indian woman entering Britain to be reunited with her fiancée in 1976 provoked outrage amongst the Asian community and sparked a campaign by the IWA demanding openness about the use of these tests (for the British government was first denying their use) and an end to the degrading practice. In coordinating this campaign, the IWA organised effectively, linking up groups in the UK and India to demand an end to this practice. IWA members made representations to the Indian government, which in turn took up the issue with the British government and the United Nations Human Rights commission. It is believed that around 80 women went through these degrading and sexist tests in the 1970s, before the British government stopped their use on immigrant women at airports in 1979. The case of the IWA’s campaign against ‘Virginity Tests’ highlights another strength of its character and network: the cooperation between various UK-based and international groups. As a group predominantly made up of immigrants, with contacts ‘back home’ and a presence in their new home, the IWA combined forces with foreign groups and bodies to create supranational campaigns.

The gradual decline of the IWA began towards the end of the 20th century, as the landscape of British politics and society changed. The deindustrialisation of the UK economy reduced the number of members, as many South Asians moved into self-employment or white-collar occupations. The membership of the Indian Workers Association was also increasingly absorbed into the more traditional political structures and groupings. A number of the key IWA members have, for example, stood for Labour in local elections or joined broader (and once somewhat discriminatory) national trade unions.

However, the IWA remains active in a number of centres across Britain. The movement still remains oriented towards anti-racist and working class politics, campaigning on issues of social and racial justice and oppression. The social and pastoral work of the IWA continues to be a particularly strong and prominent strand of its work, as well as supporting workplace politics and labour organisation. The longevity of the IWA and its continuing relevance to the lives of its members and the South Asian community are testament to the long journey it has been on and its continued place within British politics and radicalism today.

(Feature image by Rathfelder, used under the Creative Commons License)

Sources/Further Reading

Books

‘Sikhs in Britain: The Making of a Community, G. Singh, D.S. Singh, (London; New York: Zed Books, 2006)

Indians in Britain, A. Chandan, (Stosius Inc., 1986)

Coming to Coventry, Stories from the South Asian Pioneers, P. Virdee, (Herbert Gallery- Coventry Teaching PCT, 2006)

Articles

‘This is Our Home Now: Reminisces of a Panjabi Migrant in Coventry, an Interview with Anant Ram’, A. Ram, D.S. Tattle, in Oral History, Vol. 21, No. 1, (Spring 1993)

‘The Indian Workers’ Association Coventry 1938-1990: Political and Social Action’, T. Gill, in South Asian History and Culture, Vol. 4, No. 4

Online Sources

‘60 Years of Indian Workers Association, Legacy and Contribution’, IWA, Southall, B. Purewal

‘Indian Workers Association (Southall), 60 Years of Struggles and Achievements, 1956-2016’, B. Purewal

http://www.iwasouthall.org.uk/images/iwa-booklet.pdf

(Oral History) Interviews, IWA, Southall

http://www.iwasouthall.org.uk/interviews.html

‘From the archive: Airport virginity tests banned by Reese’, M. Phillips, The Guardian, (February 1979; February 2010)

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2010/feb/03/airport-virginity-tests-banned

‘Virginity tests for immigrants “reflected dark age prejudices” of 1970s Britain’, A. Travis, The Guardian, (May 2011)

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2011/may/08/virginity-tests-immigrants-prejudices-britain

‘Forty years on, Southall demands justice for killing of Blair Peach’, V. Chaudhry, The Guardian, (April 2019)

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/apr/21/southall-demands-justice-killing-of-blair-peach-1979

‘The Killing of Blair Peach’, D. Renton, London Review of Books, Vol. 36, No.10, (May 2014)

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v36/n10/david-renton/the-killing-of-blair-peach

‘How London’s Southall became “Little Punjab”’, V. Chaudhry, The Guardian, (April 2018)

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/apr/04/how-london-southall-became-little-punjab-

Ciara Garcha is a History student at the University of Oxford, from Manchester. She is on the Oxford University History Faculty’s Race Equality Action Group student steering committee and is passionate about making history more representative and inclusive of all stories and narratives. Her interests include the colonial experiences of India and Ireland, US political history, gender history and the long history of immigration to the UK.